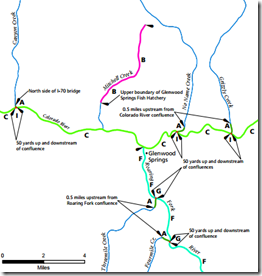

Where I live now, on Colorado’s Western Slope, towns are strung out along the confluence of two rivers, the Roaring Fork and the Colorado. Those who live “upvalley” live southward along the Roaring Fork, and generally speaking, the richer they are or the richer they want to be, the closer they live to Aspen. Those who are considered less affluent or perhaps just more blue collar in their upbringing, tend to live “downvalley” along the Colorado River from Glenwood Springs, and west toward Grand Junction.

I’m generalizing, because it’s unrelentingly beautiful everywhere in between. Plenty of people choose to live in many of these spots  due to professional considerations, personal preference, or historical connections. There are actually quite a lot of professional, artistic, and well educated people living downvalley, but some upvalley people either don’t know this or don’t like to think so.

due to professional considerations, personal preference, or historical connections. There are actually quite a lot of professional, artistic, and well educated people living downvalley, but some upvalley people either don’t know this or don’t like to think so.

I live in the middle, in Glenwood Springs, a Victorian town where the Roaring Fork and the Colorado join. If you’ve ever driven through Colorado on I-70 or come through the state on Amtrak, you’ve nicked the edge Glenwood. Perhaps you’ve stopped at the hot springs.

Often when I’m skiing upvalley, where most of the snow is, other skiers ask me where I live. When I tell them, the conversation usually just ends right there. “Oh.”

The right answer appears to be Carbondale (the next town upvalley from ours) or Basalt. (Most people think Aspen is kind of gross.) I wouldn’t mind living in Carbondale. It’s a cute town, closer to skiing, with a surprising amount going on culturally. But whenever someone does this “Oh” thing, I get my back up and feel kind of stubborn about the lower end of the valley.

So imagine how the feelings run about another town, about 20 miles downvalley, called Silt.

Silt is located in the Grand Valley, which deserves its name. Heading west on I-70 from Glenwood, you pass New Castle, the last of the semi-respectable downvalley towns. You go around a bend and the sky opens up into a wide stretch of mesas and light, light, light. Then you hit the triad of strangely named settlements. Silt, Rifle, Parachute.

We lived in Silt ourselves for a short time. I’d told my partner: Please, anything but that town. I can’t live in a place named after mud. Why would anyone call a town Silt? Not that Carbondale or Basalt are particularly attractive names, or that Aspen is all that creative when you look at any hillside in Colorado.

But as a poet, I feared Silt. It sounded like a place where people would just, well, settle. As if they didn’t care what happened to them. Even Rifle, I said, had more of a—I can’t help it—a kick to it.

The rental market around here, though, is very tight, and it’s so hard to find landlords that allow pets. We’re not ready to buy, partly because we haven’t decided on a town. So, my partner wound up choosing a house in Silt while I was out of town. It was seven miles from the job he’d taken as a public mental health therapist, in Rifle. We had a lot to learn.

When I saw the view from our mesa-top house in Silt, I had a hard time complaining:

All my life I’ve struggled to wake up in the morning. But not there. I couldn’t wait to get up and look out the window (the shot above left is sunrise on the Roan Plateau). The days were long, even in the dead of winter. A few months ago, I was back in Boulder to get my ski boots fit at Larry’s Bootfitting, and one of the customers there said, “People talk about the light in Santa Fe, but I think the light in the Grand Valley is just as good.” She was so right.

There were other charms. A few miles from the house—not a bad bike ride, or a quick drive if I wanted to take the dogs for a run on nearby trails—there was a reservoir, Harvey Gap.

Speaking of dogs, Silt has the best dog-park ever. Dogs can get right into the Colorado River, or meander through cottonwoods and thickets. Circling it twice was a 20-minute run for me.

I can say that every single day I lived in Silt, I lived in stunned appreciation for the beauty. Every bike ride had a view for each pedal stroke. Pretti Lane, for instance:

It was only about an hour to great skiing—either upvalley at Sunlight or Snowmass, or downvalley at Powderhorn:

And the climbing opportunities were also great, at the West Elks, only a fraction of which are shown here, or at Rifle Arch, or the more famous Rifle Mountain Park.

However. You need to breathe. And to drink water. That haze in the Pretti Lane shots? Coming from wildfires, which is just SOP these days in the West, but also from ozone and other toxins in the air from fracking and drilling. Whenever I turned on the washing machine, the whole house smelled like natural gas. The washing machine, not the dryer.

My mechanic told me that his kids are not allowed to drink the water in school. That’s the school’s rule. No drinking the town water.

The upvalley people, many of them environmentalists, will say: We need to drill because we must reduce our dependency on foreign energy, so we can get out of these wars. Or as another environmentalist, someone high up in Garfield County administration, put it: We need the revenue. She said, Our county is one of the most powerful in the state, and it has no debt because of oil and gas drilling.

It doesn’t seem to change their minds if you point out that we don’t HAVE ENOUGH oil and gas under our American soil to make a difference in our foreign dependency. A month ago, the US Energy Information Administration dropped its estimate of shale gas reserves by over 40%, after a flurry of internal emails last year expressed widespread reservations about the inflated optimism about the future of natural gas drilling in this country.

A friend who sells weapons navigational systems to Middle Eastern governments, US energy companies operating in the Middle East, and defense contractors told me: Middle Eastern countries have enough oil and especially natural gas to supply the world for well over a hundred years, easily. They play down supplies in order to keep prices high. Whenever they want to change US production levels, the Saudis et al simply cut their prices. That’s because the oil and gas we have cost a lot to get and to refine.

Yet, the downvalley people in Silt and neighboring towns say: Please drill. We need the jobs.

They’re right, they do need jobs. Silt, a bedroom community dependent on drilling, recreation, and construction work, with a fair amount of small-business owners who commute upvalley as far as Aspen, has one of the highest foreclosure rates in the county, perhaps in the state. It’s just that drilling doesn’t seem to be helping with that. The boom economy actually caused the problem by bringing in too many people, driving prices up, and then when the boom corrected, the costs didn’t adjust properly.

It’s always this way in the West. You wonder why anyone ever believes it will be any different. It’s like a cheating lover who promises he’ll treat you right this time.

The price a community pays for the boom time is high. Few people upvalley ever go down toward Silt or see what’s going on there. They’ll say: Oh, I know it’s beautiful. But you never know when you’ll wake up in the morning and have a drilling rig next door.

Right? We know we need the energy, but we don’t want to live with that shit.

The trouble is, most of the people who make the decisions about what to allow and what not to allow live in Glenwood Springs or further upvalley. Or all the way in Washington, DC. They don’t really see “those people” who live in Silt or Parachute. The ones who, despite all this drilling, somehow can’t keep their houses. Whose schools are closing on Fridays despite these high county revenues. Upvalley people of course hear about meth use, but it’s usually fodder for jokes and eye-rolling instead of compassion.

Few people realize the long, back-to-back shifts that gasfield workers pull, for example, and the lack of safety precautions on the rigs—probably the original driver of the meth use. Or see that when it’s reported that drilling has “moved” to, say, North Dakota, the families don’t move. The workers, usually the fathers, commute crazily back and forth, often paying as much as $2500 per month for a camper in North Dakota on top of their Colorado expenses.

Meanwhile, my partner tries to help the children in downvalley towns, many of whom experience “anxious attachment,” which in school looks a lot like attention deficit. Some of them are not learning well. They can’t sit still and can’t concentrate, because they miss their fathers and they don’t know what’s going to happen next in their lives. This is on top of losing a day of school due to closures, while their strained parents try to pay for an extra day of childcare.

(Oh, we’re not responsible for what happens with the schools, said the county official. That’s up to the local communities and the state. Hm. I thought she said Garfield County is one of the most powerful counties in the state; why can’t it use that power to get more help for local communities?)

The thing is, Garfield County also wants to sell this region on recreation. On retirement. But you can’t do that if you’re wrecking the climate with oil and gas development, or making real estate investment dicey by destroying views and water quality. Who does want to wake up and find an oil rig next to their retirement home? Policymakers have to choose a direction.

It’s always easier for county administrators to collect revenue from extractive industries and punt regulation/accountability to the feds. If you work more soberly to attract long-term businesses that will employ people steadily and provide benefits, even if wages are lower, you might bring in fewer people, more slowly, overall. But perhaps they will be the people you really want for the region. Perhaps you could essentially Ben & Jerry’s Colorado—realign attitudes, loyalties, and politics simply by treating people better. It would be an interesting experiment. These gasfield workers are amazingly loyal to energy companies who treat them like crap and quite often kill them. What would happen if you took these tribal guys and gave them good jobs?

In another community these guys might be welding ships or building One World Trade Center, under the protection of a union. Right now they’re getting drilled into the ground, blown off 5-story rigs in high winds, and having their arms torn off. They work back-to-back 12-16 hour shifts at jobs that require a lot of focus and then are judged for using meth. Most of them are contractors or subcontractors and don’t have benefits. The tech companies I’ve worked for have had to provide perfectly ergonomic workstations due to OSHA and other standards. I mean, these employers have been worried about us getting carpal tunnel. What is up with the safety enforcement for these highly profitable energy companies?

No one holds these companies accountable on just about any level. They are granted exceptions for flaring wells even when fire bans are in effect statewide. Fracking is unsafe, environmentally. The studies that initially showed that it was safe for drinking water have been discredited. And yet nothing has been done to change any practices, or simply to stop it. The longer this goes on, the harder it’s going to be to attract better alternatives to the region. Who’s going to want to come to a fracked-up place like this?

I miss Silt. I miss the light and the big sky and the fact that I couldn’t look anywhere for one second and not see something beautiful, even if I had to overlook a rig or a wellpad. Glenwood is in a narrower valley and loses daylight much faster. But the water is better, and yes, probably the people are more educated overall, and much more friendly, as I think liberal outdoorsy types often are. I’ve found a community of writers and thinkers faster. But because of the lack of light it’s harder to wake up here. And I suspect that, as far as material goes for me as a writer, there’s less here. Overall, I wish we could have stayed. I wish our landlord’s house hadn’t been foreclosed upon. I wish the air and water had been safe.

Right now there’s a big debate about allowing some drilling to take place closer to Glenwood. No one local really wants that, partly because it would be in wilderness, but mostly because it would mean more traffic through an already overly burdened city infrastructure. However, there’s a back road the big trucks could take. Guess where it goes? Through Silt.

My guess is they’ll “solve” the problem that way.

We’re a little hypocritical about energy, said a Carbondale friend. We sure are. She meant that we take it from other countries, and kill for it. I mean that we wreck small-town America for it.

But not the hip small towns. Just the places where people are asking for it.

****

For a moving portrait of the culture of oil and gas-dependent communities , please, please read Alexandra Fuller’s absolutely gripping The Legend of Colton H. Bryant, which I briefly discussed in an earlier post.

, please, please read Alexandra Fuller’s absolutely gripping The Legend of Colton H. Bryant, which I briefly discussed in an earlier post.

For more on the environmental aspects of fracking, please check out Western Resource Advocates. They also have a blog.

For more on the community perspective, visit award-winning young-adult author Peggy Tibbetts’s blog from Silt.

Maybe you don’t want to live next to a drilling rig—and I don’t blame you—but if you drive a car or have a thermostat, take a look once in a while.